Here you will find short articles by J. S. Webb to give you a taster of subjects that are covered in different parts of the book.

“Anomaly is the mother of discovery”

Entheogens, Plant Communication and Microbiology

In the following, we will trace a thread that has appeared throughout some of the earliest and lengthiest entheogen research; the relationship between humans and plants, particularly how shamans obtain knowledge of the properties of plants. We can envisage how some effects may have been discovered through simple trial and error, then passed down by word of mouth through generations. However, it is more challenging to explain how two plants that have no effect on their own but are active together were discovered. Ayahuasca is a prime example: how did these shamans discover that two distinct plants work together in this way? Psychotria viridis contains dimethyltryptamine (DMT), and Banisteriopsis caapi contains alkaloids that act as monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI). The first is ineffective when taken orally on its own, as it is broken down by enzymes in the stomach. The second is also not psychoactive, but when mixed, the inhibitor stops the enzymes from breaking down the DMT and causes the mixture to become a powerful entheogen: ayahuasca.

Out of some 80,000 or so different Amazonian plant species, it is difficult to assume this was discovered by chance. The anthropologist Jeremy Narby investigated shamanic knowledge of plants in his book The Cosmic Serpent. Narby states that “When one asks how they know these things, they say their knowledge comes directly from hallucinogenic plants.”[1] So, Narby was stuck between the modern scientific understanding of hallucinations as being illusions of the mind and the claim from shamans of gaining knowledge of plant properties through these states. There is also a ‘chicken and egg’ problem here, because to gain knowledge from plants one needs to first know which plants to consume for this knowledge. We are thus forced to assume that ingesting individual plants leads to the knowledge of how to mix other plants to induce the desired effects.

Narby turned to scientific literature on neurology and perception to decide the matter. According to our best knowledge, we don’t know how the stimuli received by our senses and processed by the brain in different areas reunite into our coherent perception of reality.[2] He concludes that if we don’t understand how we see real objects, then we know even less about perceptions that aren’t considered objectively real. Narby was searching for something that would underlie a connection between the shamans and the plant world, which could explain how they had acquired their comprehensive knowledge. He suggests that the animist view of all living things being animated by the same principle is satisfied by DNA.[3]

In light of this, he studied symbolism in different ancient cultures worldwide. Only to find the snake, two spiraling snakes, and the concept of a ladder that has been prominent throughout history and cultures, such as the ouroboros, caduceus, and the rainbow serpent of the native Australians. The serpent is also one of the most common visions in the ayahuasca experience, which Narby experienced himself; the ayahuasca vine banisteriopsis caapi also has a serpentine shape. The link was further strengthened after he found the work of a shamanic painter, Pablo Amaringo. Amaringo only paints what he sees in his ayahuasca visions; when shown by anthropologists to other shamans, they say they see the same things.

The serpentine ayahuasca vine, banisteriopsis caapi.

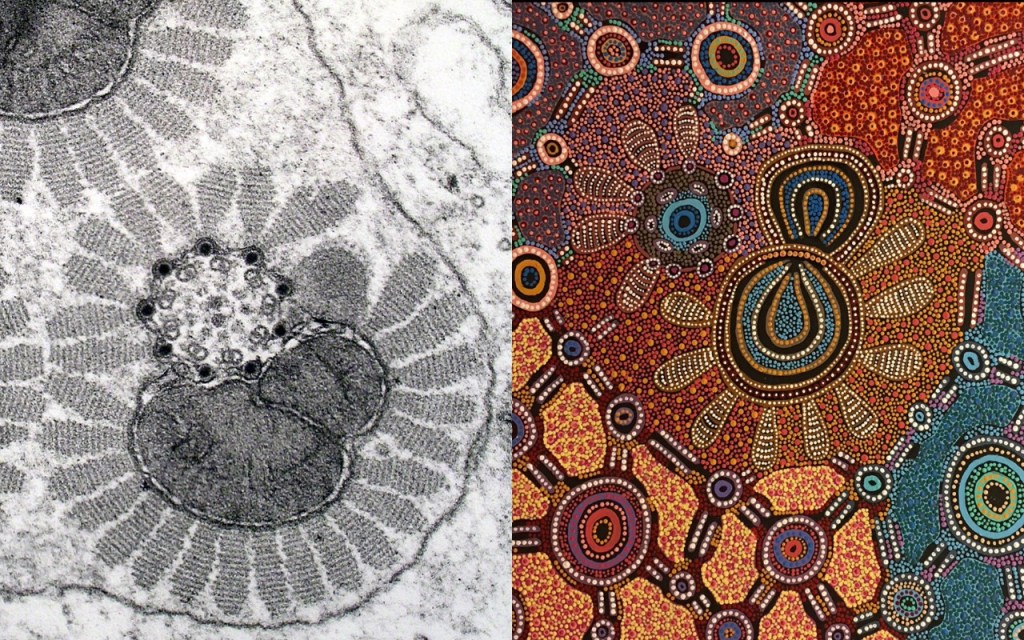

When Narby showed the paintings to a friend who knew molecular biology he said “Look, there’s collagen … and there, the axon’s embryonic network with its neurites … Those are triple helixes … This looks like chromosomes at a specific phase … There’s the spread-out form of DNA, and right next to it are DNA spools in their nucleosome structure.”[4] Thus, he supposes that the shamans who say that they learnt their knowledge of these plants and how they interact with each other through trance states may be true. An exhibition has also shown striking similarities between native Australian art and the microscopic world.[5] Native Australians use a substance called ‘Pituri’, which is chewed and can cause trance states when taken in high doses. Narby came to a working hypothesis that “shamans take their consciousness down to the molecular level and gain access to information related to DNA, which they call ‘animate essences’ or ‘spirits’.”[6] If we assume that these shamans had no knowledge of microbiological structures it is very hard to explain away how they experience these forms under the effect of entheogens.

As strange as this might sound, he went further in his research and found that biophoton emissions might be involved in this communication. The human body glimmers with its own light but it is 1000 times weaker than the human eye can detect. This results from ultra-weak photon emissions produced from changes in energy metabolism, which are called biophotons.[7] Biophotons are emitted by the cells of all organisms at a rate of around 100 units per second, and DNA is the source of the emissions. Although still poorly understood, these emissions are seen as a type of communication between cells and organisms, providing a possible channel of communication. Narby spoke to Fritz-Albert Popp, a renowned researcher in the field and asked him if there was any possible connection between biophotons and consciousness. He replied, “Yes, consciousness could be the electromagnetic field constituted by the sum of these emissions. But, as you know, our understanding of the neurological basis of consciousness is still very limited.”[8]

More recent research has found that “biophotons may play a key role in neural information processing and encoding and that biophotons may be involved in quantum brain mechanism; however, the importance of biophotons in animal intelligence, including that of human beings, is not clear.”[9] So, although the hypothesis sounds extreme, it may have an element of truth in explaining the knowledge of shamanic traditions. Narby also comments on how the quartz crystal is used in photomultipliers, which can detect biophotons; it is also used in radios, computers and many technological devices. Interestingly, they are also used by shamans in ceremonies, alchemy, witchcraft, magic, and many modern spiritual practices.

He suggests that the biophoton emissions are one and the same as the spirits that shamans communicate with, and quartz crystals are a type of amplifier used in modern technological instruments and ancient traditions. Narby comments that, if this is so, it would “mean that spirits are beings of pure light – as has always been claimed.”[10] DNA also has liquid crystalline properties, which could account for the quartz acting as an amplifier for communication. The DNA in the human body is around 125 billion miles long, which is staggering and makes for an extremely large liquid crystalline structure. The theory sounds like science fiction and is a long way from being testable, although it does propose an explanation for the incredible medicinal plant knowledge of shamanic traditions.

A completely different researcher has stumbled across a related phenomenon, although Narby seems to be unaware of this. Stanislav Grof is one of the most respected researchers of Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD); he conducted long-term clinical trials in Prague from the mid-1950s. One of the rarer LSD experiences he recorded was experiencing plant consciousness. He states, “An individual tuned into this area has the unique feeling of witnessing and consciously participating in the basic physiological processes of plants.”[11] Participants had experiences such as being a germinating seed, a leaf photosynthesizing and a root reaching out for nourishment. In surprising congruence with Narby’s theory, they also experienced processes on the molecular level. Processes include the “biochemical synthesis underlying the production of auxins, vegetable pigments, oils and sugars, aromatic substances, and various alkaloids.”[12] Grof comments that they have a very “experiential flavor”, are difficult to ascribe a source from the unconscious and that “it is not easy to discard them as fantasies.”[13]

Microscopy image of moth sperm (left) by Greg Rouse and Witchetty Grub Dreaming by Yuendumu artist Jennifer Napaljarri Lewis. (Source: University of Sydney website)

After their session, some of his participants who had these experiences became interested in the idea of vegetarianism. Others said afterwards that they had a greater appreciation for the scientific research on plant sensitivity. Grof’s subjects were not shamans, yet some of them described the same connection and understanding of plants as Narby describes. They experienced them as being them, in a first-person sense, even down to the microbiological level. This is another crumb of evidence that this type of experience is a possible source of plant knowledge in shamanic traditions.

The second related study started in 1990 when Rick Strassman performed the first prolonged study in the US into the effects of DMT. The pure DMT is administered intravenously instead of orally with an MAOI, as with ayahuasca. In a similar way to Grof’s research, there is an overlap with Narby’s theory as three volunteers described seeing DNA and other microbiology in their experience: “The visuals were dropping back into tubes, like protozoa, like the inside of a cell, seeing the DNA twirling and spiralling. They looked gelatine like, like tubes, inside which were cellular activities. It was like a microscopic view of them.”[14] These subjects are describing the same phenomenon as Grof’s subjects, describing the same structures as Narby found in shamanic art.

Another related account comes from David Luke, a prominent entheogen researcher at Greenwich University and an organiser of one of the largest conferences on the subject, Breaking Convention. He recounts an experience in Mexico under the influence of ‘the shepherdess’, the latter is the local term for Salvia Divinorum. Which other researchers have described as “the most potent naturally occurring hallucinogen.”[15] In his own words, it was “turning me rapidly into some kind of thorn bush … I found myself completely transformed into a small spiky shrub. I was quite literally rooted to the spot and could not move. Simultaneously to this, all the trees and all the plants, in fact, every blade of grass in the large field within view, began laughing hysterically … they were all cracking lines like ‘now you know what it’s like to be a plant, ha, ha, ha’ … then a disembodied voice spoke … ‘you stupid humans you think you run the show around here, you’re so arrogant, but you haven’t got a clue’ … although I had hypothetically reasoned that everything might be inherently conscious, I had never expected to be chastised by the spirit of Nature or publicly ridiculed by grass.”[16] In the same manner as Grof’s subjects Luke had a first person experience of being a plant and, in addendum, the plants communicating directly with him. This is another suggestive crumb that this form of knowledge and communication is possible.

These are all accounts of experiencing microbiology or communicating with plants during an entheogenic experience. By themselves, they seem radical, but together, they give more weight to the possibility that our relationship with plants and the effect on the mind of entheogens may be a lot stranger and more intimate than we might first assume. It seems that one of the overarching effects of entheogens is that they remind us that we are nature; not separate from it or simply part of it but one and the same as it. Another aspect to consider is scale invariance, the effect of entheogens can induce a blurring of the normal scales of things. The visuals experienced can also take fractal like forms and fractals are also scale invariant. As microbiology is at a very different scale from our normal experience this suggests another link to the validity of this phenomenon.

Recent research has discovered plant memory, intelligence and communication. A study from Australia has shown that the Mimosa pudica plant, which closes its leaves rapidly when disturbed, has a memory lasting at least a month. In the study, the plants were dropped from a height of 15cm onto a foam pad, which, although not damaging the plant, shocked it into closing its leaves. This was repeated 60 times for each training, done five times in one day. During the training, the plants slowly realized that, although shocking, the dropping wasn’t damaging. As such, closing its leaves was a waste of energy, and it reduced its photosynthesis by 40% when closed, so it eventually stopped closing them. After being left for a few days, the plants were tested again, after a week, and finally, after a month. Thus, even though there are no neurons in a plant, it somehow remembers this stimulus and how to react to it; the paper concludes that “the process of remembering may not require the conventional neural networks and pathways of animals.”[17]

Other studies have shown that slime molds have cognitive abilities similar to animals: “The advanced problem-solving capacity of the slime mold, at a level previously demonstrated only in brained organisms, provides support for the view that many ‘lower’ organisms can perform cognition-like feats in the absence of a nervous system.”[18] Substantial research has also shown that trees communicate with and through mycelium networks. They can exchange carbon and nitrogen between trees and communicate with other trees; this has been called the Wood Wide Web because a whole forest can be connected through one network. Trees can also warn other trees of insect attacks and change the bitterness of their leaves to protect themselves.[19] Therefore, it is evident that plants learn, remember, communicate, and problem-solve. This adds weight to the possibility of experience and communication with plants facilitated by entheogens. Considering this and the research we have reviewed, the seemingly absurd notion of direct experience of microbiology and plant communication under the effect of entheogens seems much more plausible.

[1] Narby, J., The Cosmic Serpent, (Penguin, New York, 1999), p. 11.

[2] Narby, The Cosmic…, p. 48.

[3] Narby, The Cosmic…, p. 61.

[4] Narby, The Cosmic…, p. 70.

[5] The University of Sydney website, https://sydney.edu.au/news-opinion/news/2018/06/13/stories-and-structures–aboriginal-art-meets-the-microscopic-wor.html accessed 3/6/2021.

[6] Narby, The Cosmic…, p. 117.

[7] Kobayashi, M., Kikuchi, D., ‘Imaging of Ultraweak Spontaneous Photon Emission from Human Body Displaying Diurnal Rhythm’, PLoS One, 4(7), (2009).

[8] Kobayashi, ‘Imaging of…,’ p. 128.

[9] Wang, Z., and colleagues, ‘Human high intelligence is involved in spectral redshift of biophotonic activities in the brain’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(31), p. 8753-8,(2016).

[10] Narby, The Cosmic…, p. 129.

[11] Grof, S., LSD Doorway to the Numinous, (Park Street Press, Vermont, 1975), p. 184.

[12] Grof, LSD Doorway…, p. 185.

[13] Grof, LSD Doorway…, p. 185.

[14] Strassman, DMT…, p. 175.

[15] Imanshahidi, M.; Hosseinzadeh, H, ‘The pharmacological effects of Salvia species on the central nervous system’, Phytotherapy Research, 20(6), p. 427-437, (2006), p. 431.

[16] Luke, D., ‘Ecopsychology and the psychedelic experience’, European Journal of Ecopsychology, 4, p. 1-8, (2013), p. 1.

[17] Gagliano, M., Renton, M., Depczynski, M., Mancuso, S., ‘Experience teaches plants to learn faster and forgot slower in environments where it matters’, Oecologia, 175, p. 63-72, (2014).

[18] Reid, C. R., and colleagues, ‘Decision-making without a brain: how an amoeboid organism solves the two-armed bandit’, Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 13:20160030, (2016). p. 7.

[19] Wohlleben, P., The Hidden Life of Trees, (William Collins, London, 2016).